Some modelers build their entire model railroad focused on a common theme. To help a beginner get an idea of this type of model railroad, brief descriptions of three such themes follow. Those themes are Narrow Gauge Railroading, Logging Railroads, and Early Rail Railroads.

Section I: Narrow Gauge Modeling

There is something about narrow-gauge modelling that gets in your blood. It's hard to define just what is. It may be the beautiful mountain scenery for the 3' narrow gauge railroads set in the Rocky Mountains such as the Denver and Rio Grande Western, the Rio Grande Southern or the Colorado & Southern to name a few.

For Maine 2' narrow gauge it may be its top-heavy, quaint, backwoods nature. Quite a number of narrow gauge lines are favorites. Yet there are quite a number around the country: The East Broad Top, a coal hauler in west central Pennsylvania, the Tweetsie or the East Tennessee and Western North Carolina and the many logging railroads prevalent in the Pacific Northwest and other regions.

That narrow-gauge railroads have a smaller gauge and proportionally smaller equipment, is what gives it a quaint, grass roots feel. The engines, mostly steam, remind us more of large pick-up trucks servicing the communities along the line than the huge semi-tractor trailer rigs analogous to mainline standard gauge railroads taking goods across the country.

Although narrow-gauge modeling remains a small percentage of total modeling population, narrow-gauge modelers make up for it with enthusiasm and highly skilled modeling. Some of the high-level modeling comes from the lack of ready-to-run models requiring the modeler to scratch build his or her cars and locomotives.

Fortunately, that is not a requirement anymore. There are many manufacturers of narrow-gauge equipment, be it 3' gauge, or some of the smaller gauges such as 30" gauge or 2' gauge.

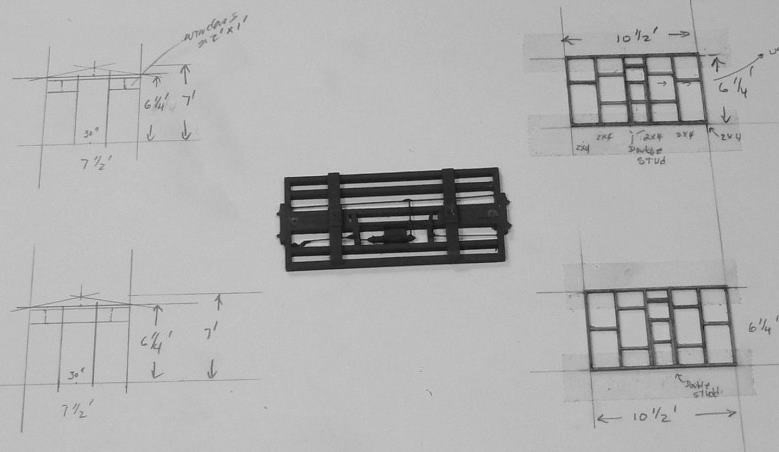

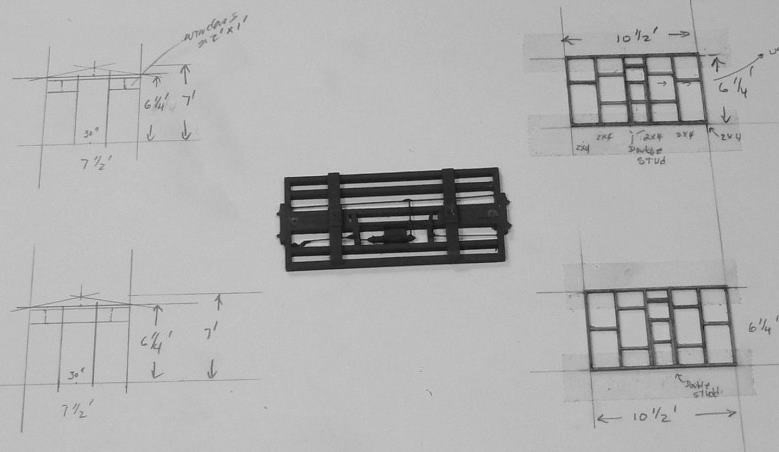

HOn3 scratch-built logging caboose in progress.

HOn3 scratch-built logging caboose in progress.

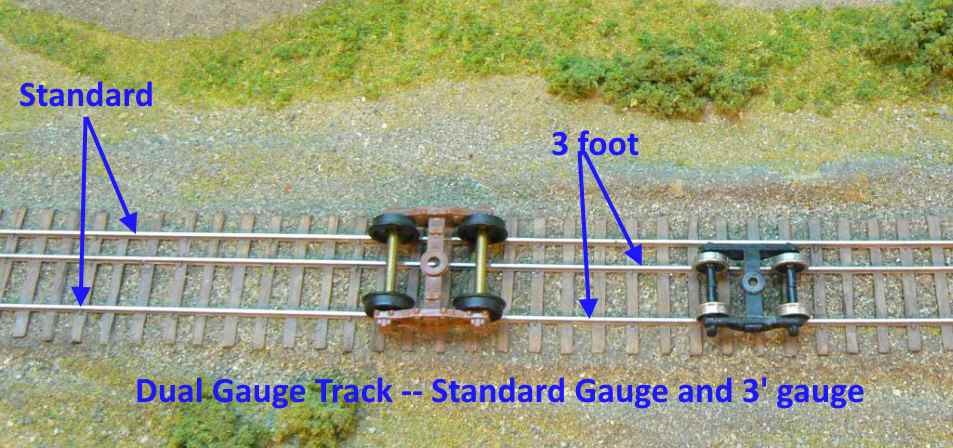

Now let's get more specific about scale and gauge. Scale refers to the ratio between any linear dimension on a prototype item to the same linear dimension on a model of that item. HO Scale has the ratio of 1:87. So, for instance, the length of an HO model of a 40' boxcar will be 1/87th of the length of the car in the real world. 40 feet is 480 inches, so the real car is 480 inches long. Its HO model would be 1/87th of that or about 5.5 inches long. (480 divided by 87). Gauge on the other hand refers to the distance between the rails on the tracks. In the real world that has been standardized to 4' 8.5”. That is 'Standard Gauge'. If on your model railroad, you place the rails closer than a scale 4' 8.5", you are modeling in 'Narrow Gauge'. In the real world, there are examples of railroads with their rails spaced at some really 'odd' distances. For instance, one logging railroad in Pennsylvania had its rails spaced 46” apart. Why that distance? Who knows? Luckily back then, the major (and some minor) locomotive manufacturers were happy to accommodate whatever gauge the owner wanted. By far, the most commonly found narrow gauges were 3', 2.5'(30"), and 2'.

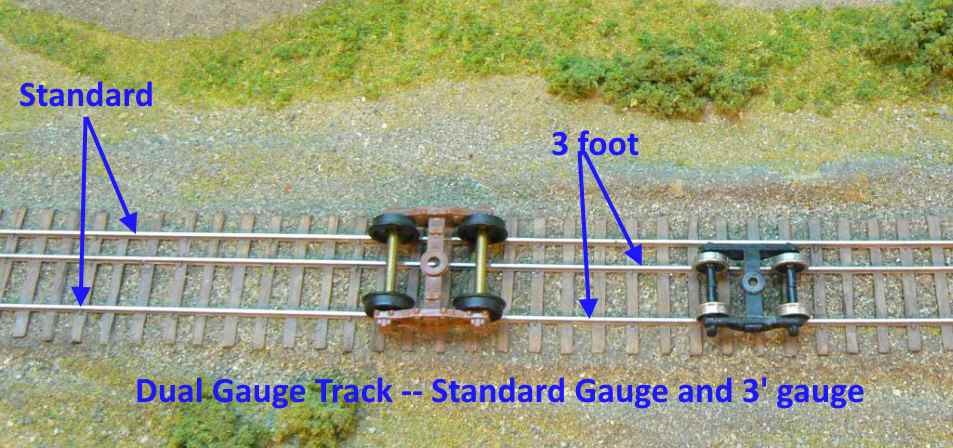

Often a narrow gauge railroad would lay some 'dual gauge' track – especially if they interchanged with a standard gauge railroad. Dual gauge track consists of three rails – the outer two spaced at 4' 8.5" (standard gauge), and a third rail in between spaced at their 'narrow gauge'.

Narrow gauge modeling exists in all major scales: HO (1/87), S (1/64), O (1/48) and F (1/20.3) which runs on No. 1 or "G" gauge track (1 3/4" gauge). There is even some 3' narrow gauge equipment for N scale. HOn3, which is the shorthand for HO scale, 3' narrow gauge, (the small "n" means narrow gauge), has a wide following with affordable cars and equipment from a variety of manufacturers. Blackstone, a division of Sound Traxx has a lot of D&RGW and RGS equipment and even some East Broad Top hoppers. Micro-Trains has some nice Colorado & Southern equipment. On30, is O scale narrow gauge with a slight compromise in gauges. The "30" is for 30" gauge, a little bit smaller than 3', (36") but a bit larger than 2' (24") gauge railroads, but the cars and engines available include those which model the popular 3' gauge lines such as the D&RGW and other equipment which is patterned after the Maine 2' gauge lines. Bachmann is one of the prime suppliers in this size. Take your choice. Sn3 has been a popular but more expensive size because much of the equipment is handcrafted in brass. Peter Built Locomotive Works, PBL for short, is a key manufacturer. Much of the original G gauge equipment was semi-scale and offered by LGB, a German manufacturer. This was followed some years later with scale equipment, which operates on G gauge track as 3' narrow gauge by Bachmann and Accucraft. As these models are quite large, they are somewhat more expensive than HOn3 or On30 equipment.

Narrow gauge track and switches are readily available for the most popular scales. A search through the websites of such manufacturers as Micro Engineering (ME), Shinohara, Peco, San Juan, LGB, and Accucraft AMS should give you a good start- depending on your scale.

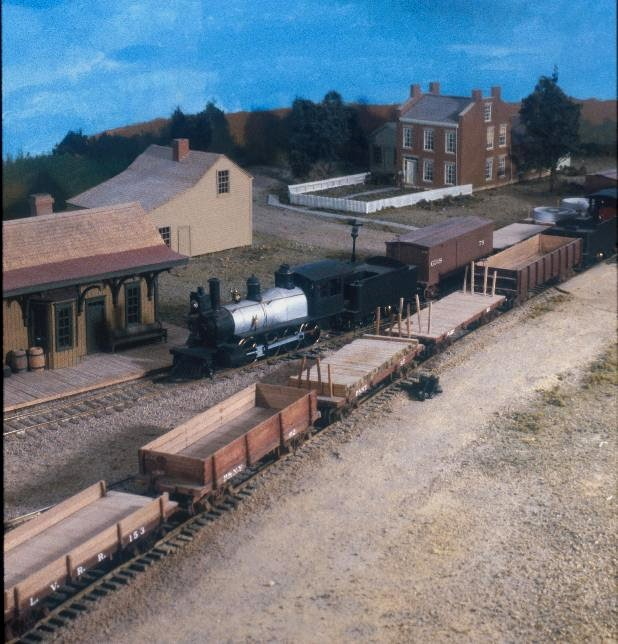

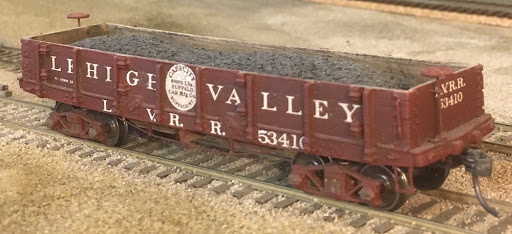

In the real world, narrow gauge rolling stock tended to be not only narrower, but also shorter and not as tall. This can be seen in the accompanying picture of two HO Scale gondola cars.

On the other hand, there is no difference in size between an HO standard gauge structure and an HOn3 structure. It is only the locomotives and rolling stock that were smaller in overall size. That makes populating your Narrow-Gauge railroad with structures as easy as if you were modeling standard gauge.

So why do modelers try to scratch the 'narrow-gauge itch'. It is probably a combination of the locations these railroads frequented and the industries they served. They often ran in the mountains or the woods, and served such industries as logging and mining. You would find them in and around quarries, slate pits, and clay works. They were prevalent in an era that seems simpler and ripe for research. And, we might say that the locomotives and rolling stock were almost 'cute'.

Section 2: Logging Railroads

Logging can become the focus of a basement filling model railroad, a side branch on a smaller model railroad, or even one module in a modular railroad. If you have limited space, picture a 2' x 6' shelf layout in HO Scale with a smaller saw mill at one end (with or without a log pond), some logging taking place in the middle, and a small Furniture Mill (Stave Mill, Clothes Pin Factory, Kindling Factory, Box Factory, Hub Factory, etc.) at the other end. Now picture a small Porter type locomotive shuttling a few cars back and forth. That could be your 'starter railroad' all by itself.

Don't want to dip your toe into 'narrow-gauge'? No problem. There were many logging railroads that were standard gauge.

Don't want to buy one of the geared locomotives (Climax, Shay, Heisler – or even the rare Dunkirk)? No problem. Many logging railroads used rod locomotives from small 0-4-0's to 2-8-0's. (The little 0-4-2 in this photo, taken at the 2015 NMRA Convention is a good example.)

How about a Forney style locomotive?

Scale? You have many choices. Logging structures, locomotives, and equipment are readily available in most of the popular scales.

What is that you say? You are not familiar with some of the wood industries mentioned above? What in the world is a 'Hub Factory'? For that matter, what is a Dunkirk locomotive? Well, one of the other things that draws model railroaders to the logging theme is the joy of the research. Just go to your favorite search engine and have at it!

Now you are relatively new to the hobby or you wouldn't be reading the Beginners' Guide. But here is a not-so-well-kept secret. Most model railroaders do not enjoy ballasting track. Not at all. Well, logging railroads did very little in the way of ballast, and certainly did not maintain well contoured roadbeds. A quick clearing of the forest floor, throw down the ties, leave them un-ballasted or just throw forest floor debris between the ties. Why worry? That hill up ahead would be cleared of wood soon, and those tracks would be torn up and re-laid elsewhere.

Look at this picture from one of Tom Taber's books on the "Logging Railroad Era of Logging in Pennsylvania" and used with permission. Look at the flat contour of the roadbed and the 'junk' between the ties. Now look at the buildings – wood. Unpainted wood. Why paint, those are only temporary structures. Ever want to try your hand at scratch building, but were afraid that the results might be a bit 'crude'? Well they would be great in a logging camp.

Structures

If you decide to model a logging railroad, you could include the nearest town as part of what you model. It would include stores, housing, a school and a church or two. Or, you can limit the focus of your modeling to a saw mill and associated structures. Your choice.

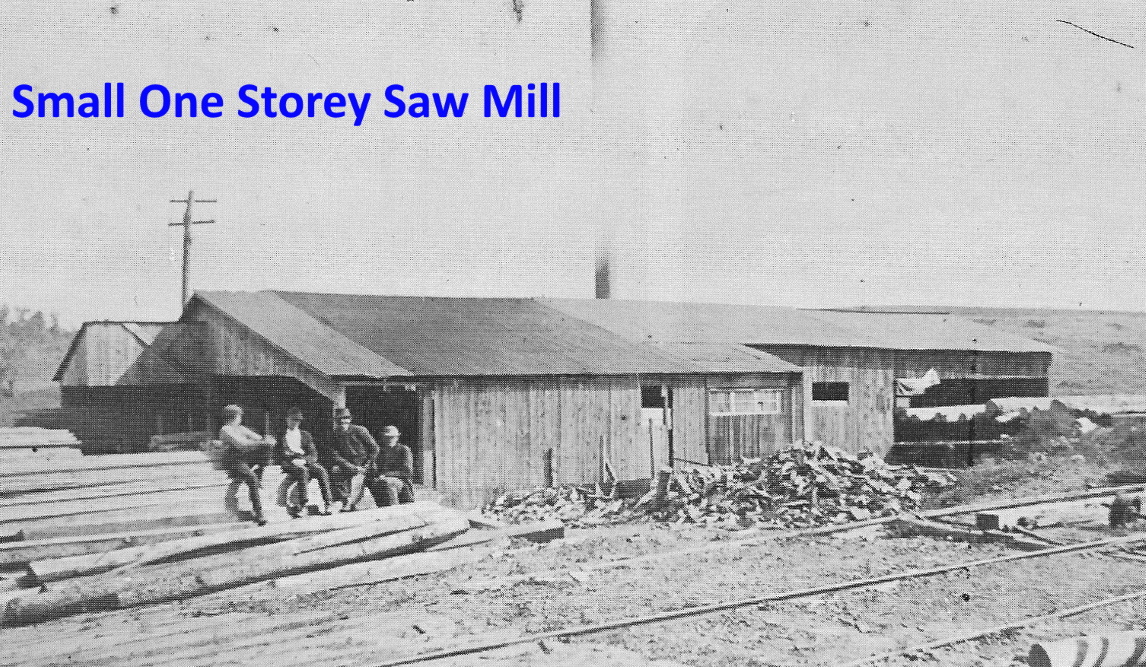

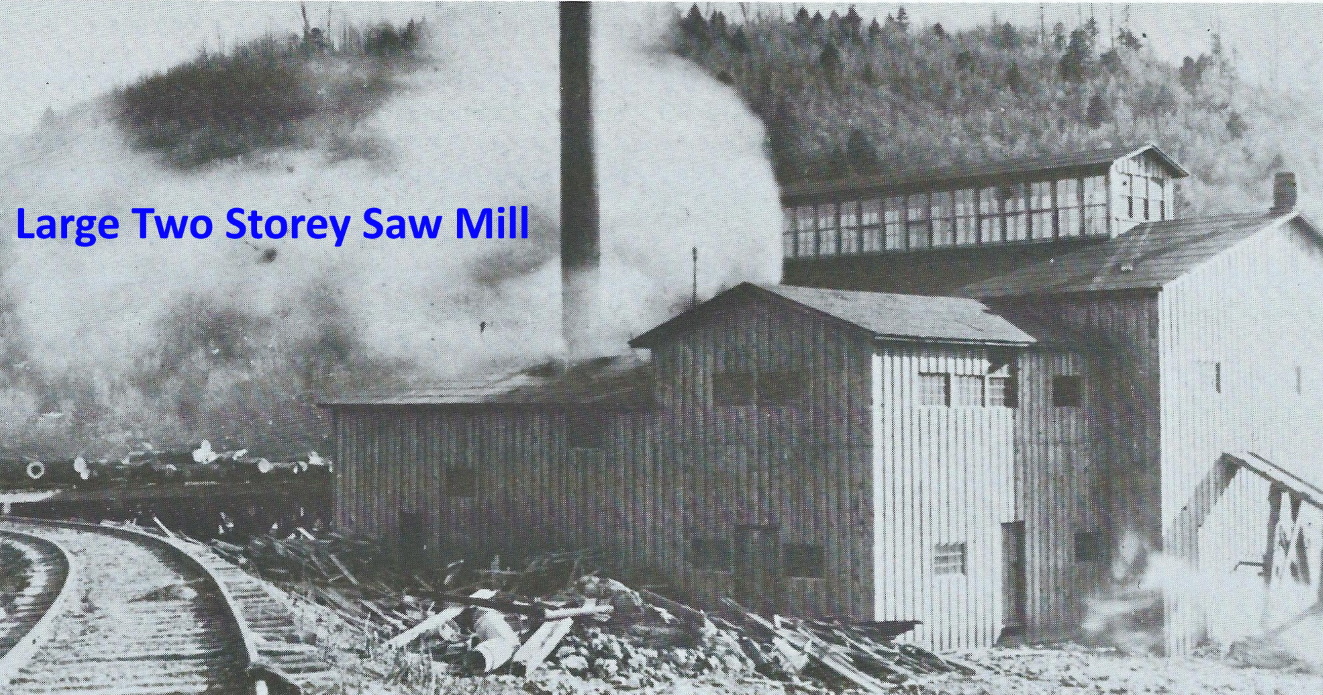

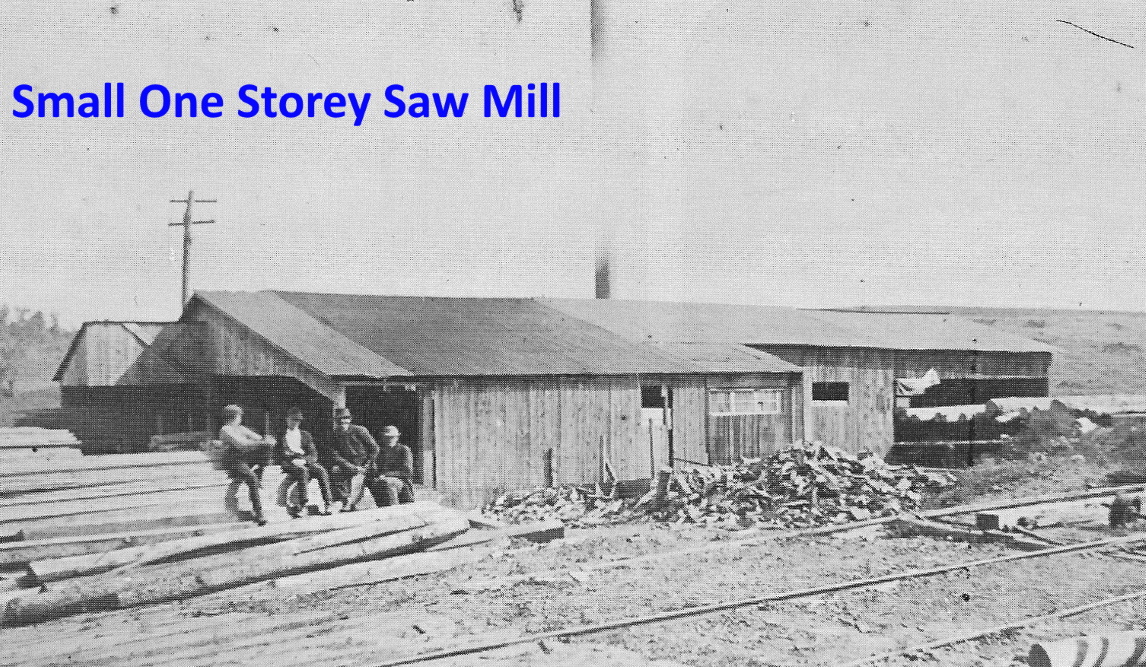

Saw mills varied in size. Some of the smaller ones were one storey tall and had the steam engine in an attached or adjacent structure. Mid-size and large mills were usually two storeys tall with the mechanisms driving the saws on the lower level.

These photos were also taken from Tom Taber's books on the "Logging Railroad Era of Logging in Pennsylvania" and used with permission.

These photos were also taken from Tom Taber's books on the "Logging Railroad Era of Logging in Pennsylvania" and used with permission.

Kits to build saw mills – both large and small - are available in most scales. Once installed on a model railroad with scenery all around it, a saw mill can become a focal point of the entire scene as the following two photos illustrate. The fire photo, the one with the slash burner in the background, was taken on Doc Patti's On3 Winged Foot & Western RR. The second photo was taken on Tom McInerney's HO/HOn3 Elk River RR. (Both photos taken by Bruce DeYoung, MMR®)

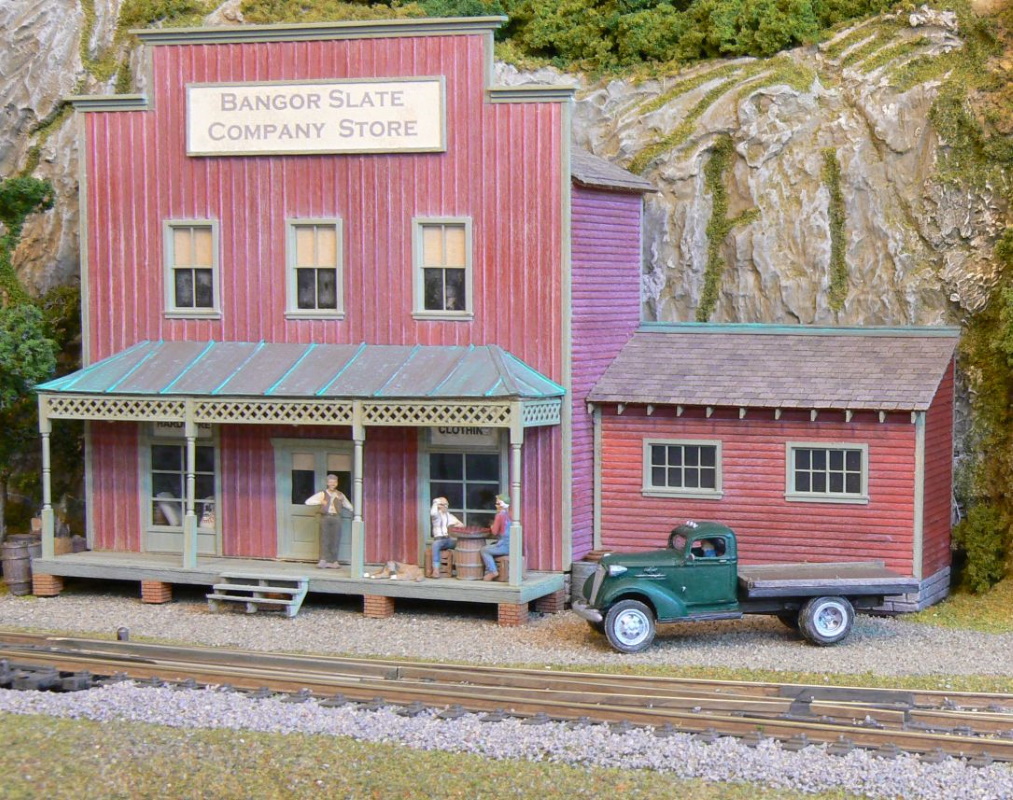

In addition to the saw mill, you might want to add some housing for the mill workers and a store where they can purchase their necessities. Many logging companies, like many mining companies, provided both of these “amenities”. In the case of the housing, all the houses had a common design. Company stores varied in design, but a covered porch the full length of the front of the building was common. The following two pictures illustrate these structures.

The Company Housing picture was taken on Ted Pamperin's HOn3 Railroad and the Company Store picture was taken on Bruce DeYoung's HO scale RR. Both pictures were taken by Bruce DeYoung, MMR®.

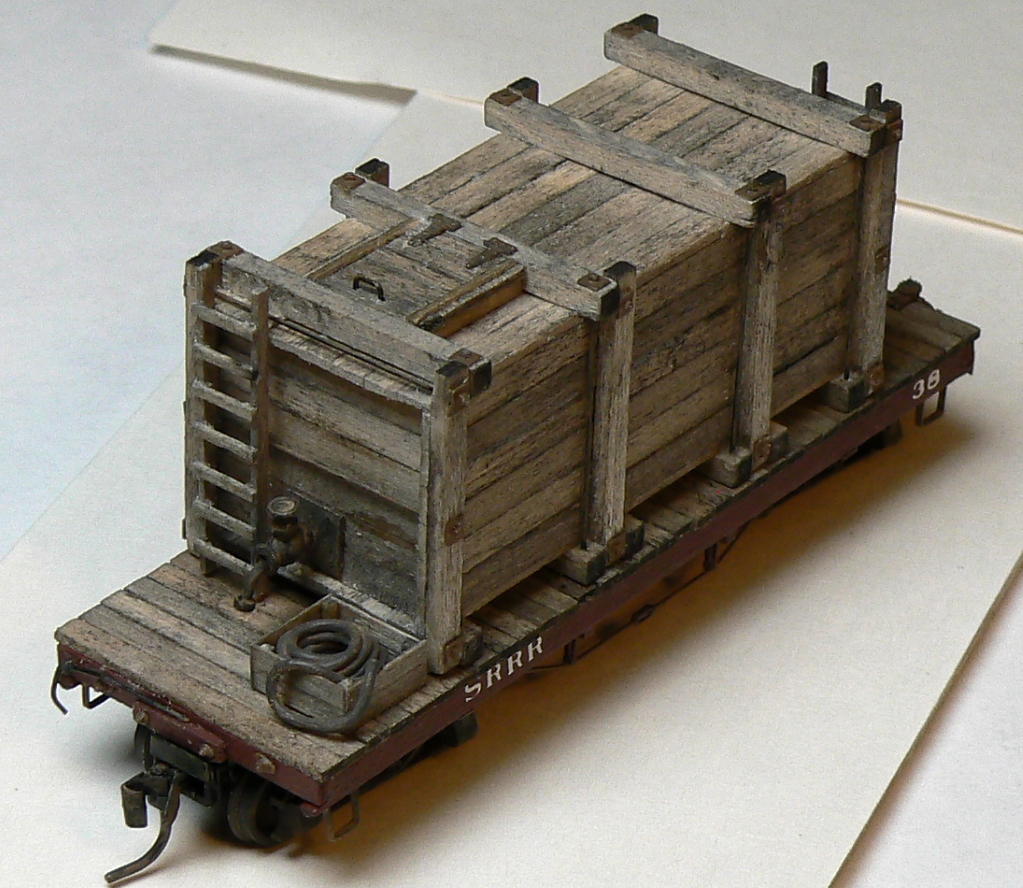

Rolling Stock

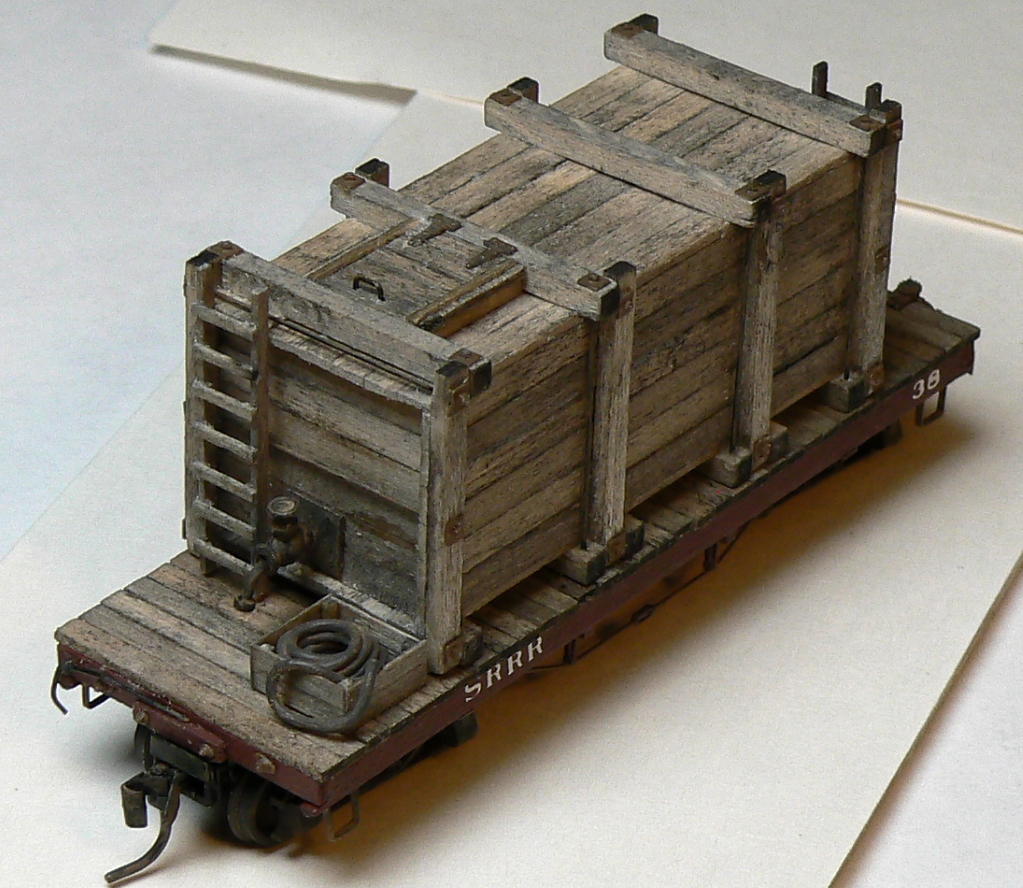

Another appeal of modeling a logging railroad is the variety of interesting rolling stock often found in use. Much of the rolling stock was built or modified on site, and thus was unique to the railroad. The following pictures are all located on Bruce DeYoung's HOn3 Slate Run Railroad. Almost all are scratch built.

Log Car

Log Car

The logs are made from branches from a Mountain Laurel bush.

Below: A flatcar with bulkhead ends added in the 'backshop' carries a load of pulpwood. The wood load is again made from Mountain Laurel branches.

A scratch built HOn3 Water Car

A scratch built HOn3 Water Car

Scratch built logging caboose behind a Forney locomotive

Scratch built logging caboose behind a Forney locomotive

Videos and On-Line Resources

Section 3: Early Rail

Early Rail is a name coined by aficionados to mean railroading before 1900, or at latest, before World War I. The period 1890 to WWI was one of transition from small locomotives with a limited number of wheel arrangements, wooden rolling stock, and many small railroads, to large regional systems.

This period has an appeal to modelers interested in the history of railroading, the development of technology associated with the railroads, early industries, and the sometimes-quaint look of the equipment. There are some practical reasons for modeling the pre-1900 period. The equipment was small. Locomotives generally had four to six driver axles. The average car body was only 28 to 34 feet in length and even shorter for the decade after the American Civil War. For a given a length of track one can fit almost twice as many cars from the 1860's as compared with the 1960's.

Limited space for a layout tempts the builder to scrimp on radius size and neglect smooth transitions from straight into curves. Early motive power and cars allow for smaller radii. A 4-4-0 heading up 28' cars looks and runs just fine on 20” radius track. Even early passenger equipment can look good running on small radius track as long as the builder uses smooth transitions in track.

Trains often tended to be short, or at least do not look unrealistically short with a small number of cars. This means yard tracks, passing tracks, and mainlines can be shorter, again a savings in space.

Similar to the twentieth Century, there was a variety of car types. Some were more commonly seen back then compared with – for example - the 1950's. Stock cars appeared on many railroad rosters before 1900, but declined in numbers after the early 1900's and were run on few railroads by the end of the Twentieth Century. With no plastic pellets to be shipped and grain transported loose or bagged in boxcars, there were no covered hoppers back then.

Early rail has its challenges, most noticeably the limited range of locomotives, rolling stock and educational material. For this reason, much of this section looks at sources for appropriate equipment and information. Modeling early railroading requires some compromises, especially at the beginning when the modeler want to get trains running. But the challenges can push the modeler into new areas of knowledge and skill, perhaps another plus for Early Rail.

Motive Power

Much of the appeal for modeling the early days of railroading is the steam locomotive, whether gaily painted in multiple colors or a workaday black and Russian iron. Four wheel arrangements dominated the railroad scene in the latter half of the Nineteenth Century. Before the Civil War the most common wheel arrangement was the “American” or 4-4-0. Mountainous railroads had developed other wheel arrangements to battle gravity, such as the 0-8-0 “Camels” of the Baltimore and Ohio. The 2-6-0 and 2-8-0 wheel arrangements could be seen in small numbers, but the leading pair of wheels was rigid. The first 2-8-0 with non-rigid leading wheels was apparently designed by the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1866 and named the “Consolidation” because at the time the railroad was incorporating a number of smaller lines. The name stuck. It was suited for pulling heavy freight trains. The 2-6-0 “Mogul.” was developed about the same time. The 4-6-0 or “Ten Wheeler” was used often as an all-purpose locomotive, suited for both fast freight or passenger service, depending on driver diameter.

All of these types are available on the new or used market in HO. They might require some reworking to make them appropriate for the decade being modelled, but certainly acceptable to the modeler wanting a general look. Bachmann sells a couple versions of the 4-4-0 that appear to fit the 1870's and 80's; the newer version runs well and looks good. Bachmann also manufactures more modern Americans appropriate to the post-1900 period that could be used as is or back-dated a decade.

Bachman Locomotive pulling a kit-built LaBelle passenger car

Bachman Locomotive pulling a kit-built LaBelle passenger car

Athearn Locomotive pulling B.T.S rolling stock built from kits

Athearn Locomotive pulling B.T.S rolling stock built from kits

Athearn sold a 2-8-0 consolidation based on a Baldwin prototype that has features of the 1890's, although the pilot appears to represent a later decade. Out of stock at the time of this writing, the models are available from dealers online. Bachmann makes a 4-6-0 representing a post-1900 locomotive that would be a good stand-in for the 1890's, especially if the Walschaerts valve gear was removed or replaced.

In N scale, Bachmann offers a 4-4-0 of the 1870's-80's and Athearn a 2-8-0 and 2-6-0 similar in appearance to their HO models. In O scale, mid- and late-century Americans are available in toy train and scale versions from manufacturers.

In the United Kingdom, locomotives of many wheel arrangements and prototypes are available from manufacturers such as Hornby, Dapol, and Bachmann in several scales. For those interested in the early days of railroading, Hornby has released models of Stephenson's Rocket and passenger cars in OO (1:72) scale.

Older, out of production models can be obtained at train shows and online, including Americans and Ten wheelers. Many of these are about 10% oversized, reflecting tooling of several decades ago when larger motors were the rule. The modeler using anything smaller than code 100 rail should be aware that many models of European make had oversized wheel flanges.

The small locomotives of the Nineteenth Century can be found in brass manufactured several decades ago. Prices can often be reasonable, especially if needing new paint or small repairs. Some run well, others need work, including new motors. Many never left their boxes.

34' cars built from LaBelle (left) and Bitter Creek kits

34' cars built from LaBelle (left) and Bitter Creek kits

Rolling Stock

Typical freight cars around the time of the American Civil War and the decade following rarely exceeded 24-25 feet in length. The 1870's brought the need for larger cars in the range of 28-30' in length. The trend to larger cars led to the 34' car becoming almost a standard in the late 1880's through the 90's, eventually succeeded by 36' cars at century's end.

Car design evolved as well. Early gondolas had low, one board sides and ends, and developed into high-sided gondolas. Coal-hauling railroads bought gondolas with drop doors or hoppers in the bottom which also be used for hauling other commodities such as lumber. The northeastern coal lines would have large fleets of small 4-wheel hopper cars called "jimmies." By the end of the century wood hoppers had replaced the jimmies and many gondolas.

Hoppers had the advantage of being self-clearing but were unsuited for hauling anything but loose material.

Some relatively lightweight freight such as carriages and furniture called for large volume boxcars, as much as 50' in length and in the range of 12' tall. Many midwestern lines and some eastern lines had fleets of these cars, especially as the Michigan furniture industry took off at the end of the century. Often owned or leased by individual manufacturers, these cars were sometimes painted to be rolling billboards.

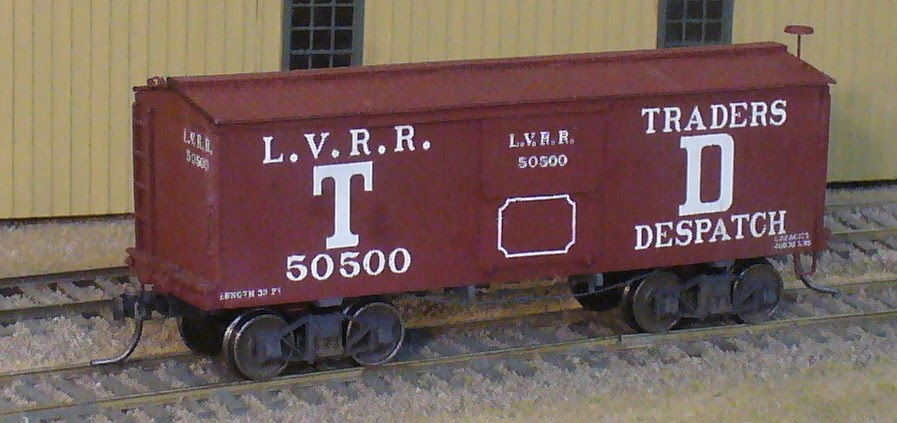

This was the period of the fast freight lines, representing cooperative arrangements among otherwise competing railroads. These were largely ordinary boxcars, but they were often painted with distinctive lettering, heralds, or colors.

Passenger cars also evolved in style and length. The clerestory became ubiquitous on American passenger cars, the so-called “duckbill” roof of mid-century giving way to the “bullnose” roof. Colors changed from light colors such as straw yellow, to a dark brown, to a dark green.

Available models include a limited number of ready-to-run flats, gondolas, stock and boxcars in HO scale. Bachmann makes a 34' boxcar apparently based on a Missouri Pacific prototype. Models representing older, shorter cars are readily found at train shows but are generally out of production. Similarly, a wider range of passenger car lengths and style show up regularly for sale. Some modelers improve the looks of ready to run models by replacing oversized door hardware and scraping off and replacing molded-on grab irons.

A good option for creating a varied fleet of reasonably detailed models is to build kits. The selection available to the modeler includes most types of freight cars in the second half of the 1800's, including box cars, flats, gondolas, jimmies, stock cars, refrigerator cars, tank cars, and passenger cars. The modeler can find boxcars, flats, and gondolas in HO, S, and O scales. The boxcar can be purchased in 25, 28, and 34' lengths, in the case of the smallest cars with a round or peaked roof. The model railroader capable of laying smooth track, creating scenery, and building simple structure kits should be able to build these kits, which come with clear, detailed instructions and are fun to build. Many are laser kits in which the interlocking components virtually guarantee easy and precise construction. Kits avoid the problems of ready-to-run models of early cars with oversize door hardware and molded-on details.

Once you are comfortable building kits you could try your hand at scratchbuilding.

The Right of Way

Most of the rules and habits we formed in tracklaying apply to the 1800's. Track built by the large railroads was well maintained and groomed, with substantial ballast. Smaller railroads often built mainlines in a hurry to get trains running and to earn some income before the money to build ran out. These tracks could be built to a low standard, but if the railroad was folded into a larger one, the first task was track replacement. The two big differences between Nineteenth Century and modern times was use of stub switches and the size of rail. The limitation of the stub switch became obvious and few lasted on mainlines much past the Civil War, although they remained in use in yards and lightly-traveled branchlines. Therefore, the Early Rail modeler can generally use commercially-available track and conventional turnouts. Where track appearance can be improved is the size of rail. Code 100 looks oversize and many modelers of post Civil War railroads go to code 83 or code 70. Even these are oversized but practical. The modeler can reduce the apparent size by painting the sides of the rail a dark brown to rusty brown color; this is generally good advice in any case to make track look more realistic. Of course, hand laying track and turnouts is always an option, even for the beginner having the right skills.

Structures

Rules for selecting and buying appropriate structures apply equally to the Nineteenth Century as they do for today, with perhaps a few more restrictions. Obviously, the march of time creates one of those restrictions; the modeler must be at least a little knowledgeable of changes in architecture and building materials. Cinder block and poured concrete buildings do not belong in the 1800's. Brick and wood ruled the day, with both clapboard and board and batten appropriate throughout the period, shiplap wood siding near the end.

Regionalism in architecture was very much part of the visual environment, city and rural. Some areas are characterized by brick, especially in cities that mandated masonry. Prevalence of brick or wood in newly settled states depended in part on local building materials; not every area is rich in sand and clay needed for economical brick construction. Similarly, stone was a rare building material for domestic use outside the northeast before dressed stone became a choice building material for government and commercial buildings and transportation could efficiently move it all over the country. Although most of us associate board and batten construction with the wild west or backwoods shortlines, it was in fact used frequently in building throughout much of the country, including railroad structures and factories.

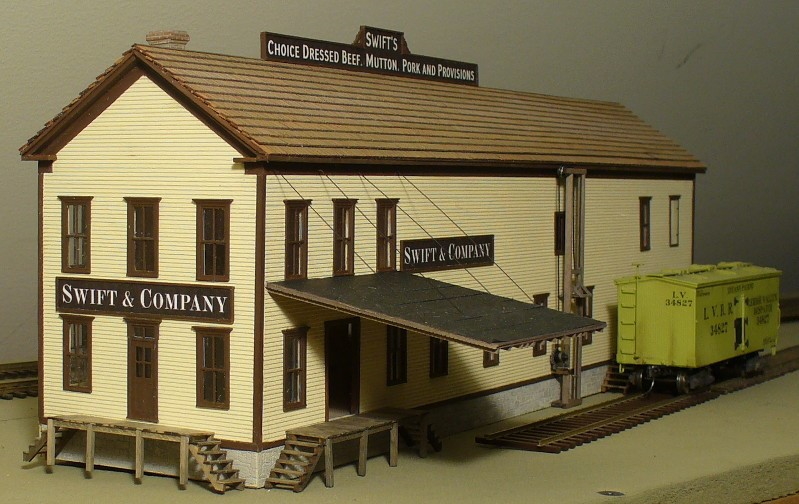

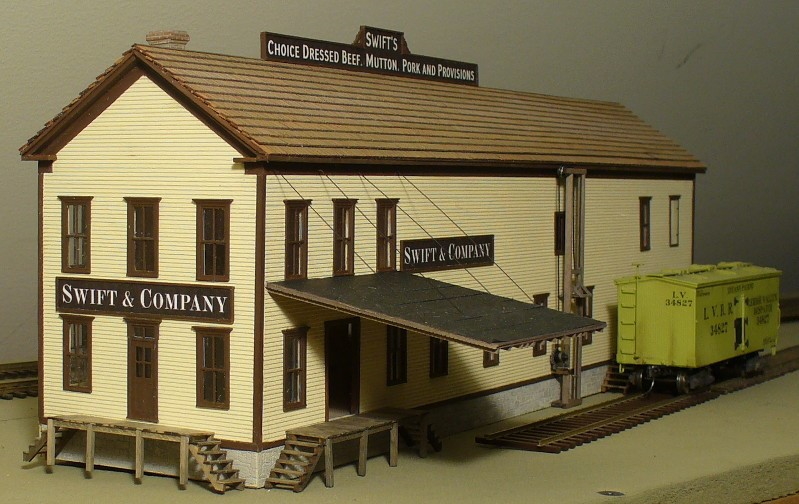

Some businesses and industries have changed in appearance or have largely disappeared altogether. With the rise of Armour and Swift, every city small or large had at least one meat packing plant or distributor, and these seem to have followed the pattern of a long narrow building. Even small towns had coal trestles or sheds to supply fuel for homes and businesses.

The modeler will find many kits appropriate to the Early Rail time period in both styrene and wood, the job being to select ones that fit a specific place and time. The best advice is to develop an eye, study photographs of the prototype, and learn. A good source of information with many examples is:

A Field Guide to American Houses: The Definitive Guide to Identifying and Understanding America's Domestic Architecture by Virginia McAlester and Lee McAlester (1984) or the second edition: A Field Guide to American Houses: The Definitive Guide to Identifying and Understanding America's Domestic Architecture by Virginia McAlester (2015).

Nineteenth Century houses and commercial buildings were distinctive in the use of paint. Information and many illustrations are in the book by Roger W. Moss and Gail Caskey Winkler: Victorian Exterior Decoration.

A rich source of photographs, engineering drawings of historical buildings, and other materials is the

Library of Congress digital collections (

https://loc.gov/collections/). Some of the larger city, state, and university libraries host regional collections.

The 1893 book by Walter G. Berg, Buildings and Structures of American Railroads: A Reference Book for Railroad Managers, Superintendents, Master Mechanics, Engineers, Architects, and Students is available in reprint and online.

Early Rail shares with narrow gauge and logging railroad modeling many of the same features and advantages. Equipment is small, track can appear to be very casually built, smaller radii are acceptable, and the builder is often driven to researching their area of interest. More can be built in a small area. These areas always encourage the model to try building kits and perhaps eventually scratch building structures and rolling stock. These three areas are not at all mutually exclusive. Indeed some beautiful models of late 19th century narrow gauge logging railroads have been built.

Additional Resources

- John H. White Jr., 1997, American Locomotives: An Engineering History, 1830-1880 Revised & enlarged Edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, 624p.

- John H. White Jr., 1985, The American Railroad Passenger Car. Johns Hopkins University Press, 704p.

- John H. White Jr., 1993, The American Railroad Freight Car: From the Wood-Car Era to the Coming of Steel. Johns Hopkins University Press, 656p.

- Anthony J. Bianculli, 2001, Trains and Technology: Locomotives. University of Delaware Press, 248p.

- Anthony J. Bianculli, 2001, Trains and Technology: Cars. University of Delaware Press, 256p.

- Anthony J. Bianculli, 2001, Trains and Technology: Track and Structures. University of Delaware Press, 240p.

- Anthony J. Bianculli, 2001, Trains and Technology: Bridges and Tunnels, Signals. University of Delaware Press, 224p.

Download Part 0 - Part 2 in one pdf